Do Christians and Muslims worship the same god? Many are inclined to think that trinitarian Christian and Islamic theologies are just too different for the two groups to even be referring to the same being. But as many have pointed out, be careful with that argument! For one thing, it may give you the unwanted conclusion that various Christian groups aren’t talking about the same god. And as many have pointed out, it’s always been part of Christian belief that the God we Christians worship is none other than the god of the Jews. My friend the Maverick Philosopher recently stated,

Do Christians and Muslims worship the same god? Many are inclined to think that trinitarian Christian and Islamic theologies are just too different for the two groups to even be referring to the same being. But as many have pointed out, be careful with that argument! For one thing, it may give you the unwanted conclusion that various Christian groups aren’t talking about the same god. And as many have pointed out, it’s always been part of Christian belief that the God we Christians worship is none other than the god of the Jews. My friend the Maverick Philosopher recently stated,

…I myself am strongly tempted to deny that Jews and Christians worship the same God — assuming that the Jewish God is non-triune and explicitly determined to be such by Jews — and what I am strongly tempted to do strikes me as entirely possible and rationally justifiable. Why can’t someone reasonably deny that Jews and Christians worship the same God?

I would urge my friend to resist this temptation. I was struck by this passage recently, from Acts 4. John and Paul have been arrested because of their preaching, and have been brought before the Sanhedrin, the Jewish council of elders, that had a degree of autonomy under Roman rule to deal with Jewish matters.

When they had made the prisoners stand in their midst, they inquired, “By what power or by what name did you do this?” Then Peter, filled with the Holy Spirit, said to them, “Rulers of the people and elders, if we are questioned today because of a good deed done to someone who was sick and are asked how this man has been healed, let it be known to all of you, and to all the people of Israel, that this man is standing before you in good health by the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead.

Notice that this is a dispute among Jews. Peter doesn’t reply that this council is irrelevant to him because he’s not a Jew. He is one, in his own mind, and in the minds of his interrogators. The Jewish context means there is no dispute whatever about the reference of “God” here. Who’s that? Obviously, Yahweh, the god of the Jews, whom they believe to be the one true god, creator of all else. The Sanhedrin is in quite a pickle, according to this text. They can’t deny that these men have wrought a miracle in the name of this Jesus. They order them men to stop preaching this new message. Peter and John famously reply,

“Whether it is right in God’s sight to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge; for we cannot keep from speaking about what we have seen and heard.”

Which “God”? Again, obviously Yahweh, the unique god of the Jewish Bible – the one Jesus prayed to as “Father” and acknowledged as his god.

And having been released, the John and Peter pray with their fellow Jesus-followers,

“Sovereign Lord, who made the heaven and the earth, the sea, and everything in them, it is you who said by the Holy Spirit through our ancestor David, your servant:

‘Why did the Gentiles rage,

and the peoples imagine vain things?

The kings of the earth took their stand,

and the rulers have gathered together

against the Lord and against his Messiah.’

“The Sovereign Lord” and “the Lord” here whose Messiah Jesus is – obviously, this is the God of Judaism, Yahweh. I won’t belabor the point, but all the New Testament, and all mainstream Christian tradition (a notable exception being Marcionism) holds that Christians are talking about the same god the Jewish Bible is. (Admittedly, some fourth century “fathers” confused the issue by urging that Jewish monotheism was false, and that their trinitarian theology was somehow a happy medium between monotheism and polytheism.) Incidentally, this “God” in both OT and NT is meant to be a god; I don’t grant that he might turn out to be some ineffable ultimate such as “Being Itself.”

“The Sovereign Lord” and “the Lord” here whose Messiah Jesus is – obviously, this is the God of Judaism, Yahweh. I won’t belabor the point, but all the New Testament, and all mainstream Christian tradition (a notable exception being Marcionism) holds that Christians are talking about the same god the Jewish Bible is. (Admittedly, some fourth century “fathers” confused the issue by urging that Jewish monotheism was false, and that their trinitarian theology was somehow a happy medium between monotheism and polytheism.) Incidentally, this “God” in both OT and NT is meant to be a god; I don’t grant that he might turn out to be some ineffable ultimate such as “Being Itself.”

So the Christian who wants to say that “Allah” (in an Islamic context) doesn’t refer to God really is hard pressed to say why “the LORD” (in a Jewish context) nonetheless refers to God. If non- or anti-trinitarian assumptions imply that “Allah” doesn’t refer to God, then why wouldn’t they imply that the Jew’s “the LORD” doesn’t apply to God? But if you say this latter, you go hard against apostolic tradition, and indeed, against Jesus. (See Mark 12:26-34)

Some wave their hands here and urge that Christianity is more closely related to Judaism than Islam is to either. True, but not relevant.

If you are a Christian, and you have a theory of reference which implies that the Christian “God” and the Jewish “the LORD” don’t co-refer, well, you have a faith-reason conflict. I don’t have such a theory, so I’m spared for now dealing with that particular conflict. My friend Bill thinks that he does have such a theory. I would only point out that this Christian commitment is a reason to reconsider such a theory of reference.

Briefly, another near-universal Christian commitment which is relevant is belief in general revelation, information that God makes available about himself to all humans at all times and places. You see this idea assumed, for instance, in Psalm 19:1-4 and in Romans 1:18-23. As even Hume granted, it is very easy, and very common to put it mildly, for people to form the thought that “Someone made all of this (i.e. the whole physical universe).” If we’re built, so to speak, to respond in this way, it would seem that we are indirectly interacting with God in so responding. Because of the beauty he put into the cosmos, and because he made us sensitive to it and inclined to respond as above, then he is indirectly interacting with us, or at least holding out the possibility of such interaction. If we so respond, wouldn’t we thereby refer to God, via a description like “creator of the heavens and the earth”? According to Paul, this is available to “the Gentiles,” i.e. to all the nations, all the people-groups. This would included the Arabs, of course, and all the rest of the Muslims. And they have always centrally claimed that their “Allah” is the creator.

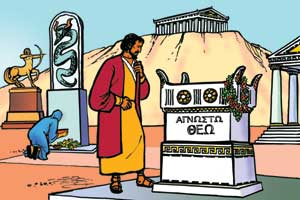

Note also the famous argument of Paul in Acts 17:16-34. One might object that Paul is merely making a rhetorical move with this “unknown god” business. But even if that’s so, notice that immediately after, he appeals to “The God who made the world and everything in… the Lord of heaven and earth” as if they ought to grant that they’ve heard of or thought about such before, and even have grounds to acknowledge his existence.

Note also the famous argument of Paul in Acts 17:16-34. One might object that Paul is merely making a rhetorical move with this “unknown god” business. But even if that’s so, notice that immediately after, he appeals to “The God who made the world and everything in… the Lord of heaven and earth” as if they ought to grant that they’ve heard of or thought about such before, and even have grounds to acknowledge his existence.

So I would ask my Athenian-Arizonan friend Bill: if this is right, then on your theory of reference wouldn’t they – the Musilm or the Athenian who has responded to general revelation via nature – be referring to God?